Isn’t traveling light always the best way to go?

During World War II, real estate on flights overseas was at a premium. The sacks of letters that went back and forth between troops and the homefront took up space that was needed for war supplies.

The powers that be knew how important for morale these letters were, however. A letter from home “strengthens fortitude, enlivens patriotism [and] makes loneliness endurable,” as a 1942 report put it.

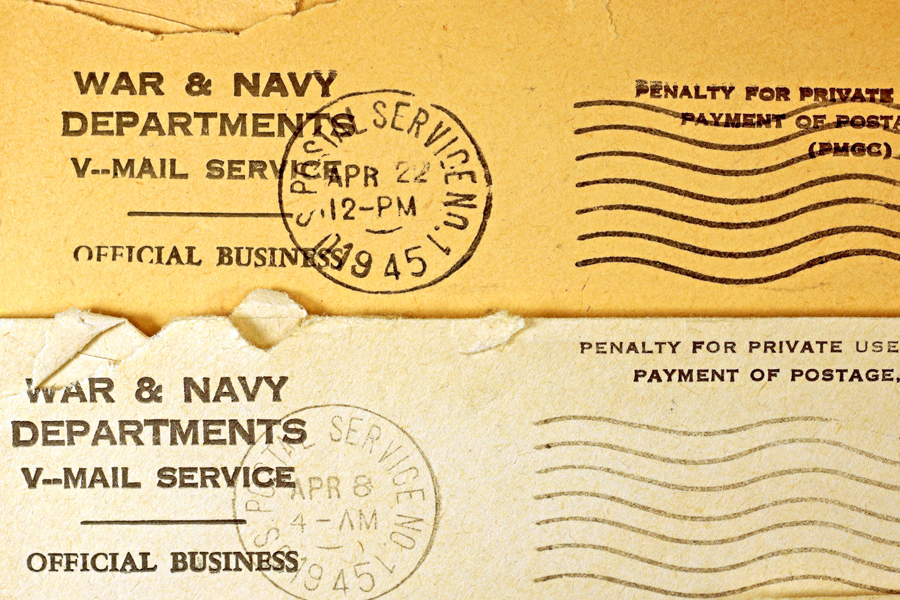

To solve the dilemma, the United States took a page from Airgraph Ltd., which the British Post Office launched in partnership with Kodak in 1941. The United States called its version Victory Mail, or V-Mail.

With a few slight changes, the services were the same: A special stationery form was used for the letter, which was then photographed onto microfilm. The microfilm was flown overseas and printed out on another form, which was delivered to the recipient.

V-Mail was launched on June 15, 1942, and ran through April 1, 1945. In that time, more than a billion letters were sent using the process.

There were limitations, to be sure. To save paper, the final letter that was delivered was a quarter to half the size of the original. Some stores sold special V-Mail magnifying glasses.

Troops’ letters were censored to ensure that no strategic information was leaked.

No enclosures were permitted, and even a lipstick kiss on a V-Mail form — known as the “Scarlet Scourge” — would gum up the works.

Still, while most letters were still sent the usual way, it has been estimated that V-Mail freed up almost 98 percent of the weight and space that the equivalent paper letters would have taken up.

Writing in Naval History Magazine, Thomas Wildenberg noted that collectors are growing interested in V-Mail letters.

“These wonderful mementos of a bygone era help us understand the past while preserving the memory of those who served in World War II.”

The “History” column appears occasionally in Link.