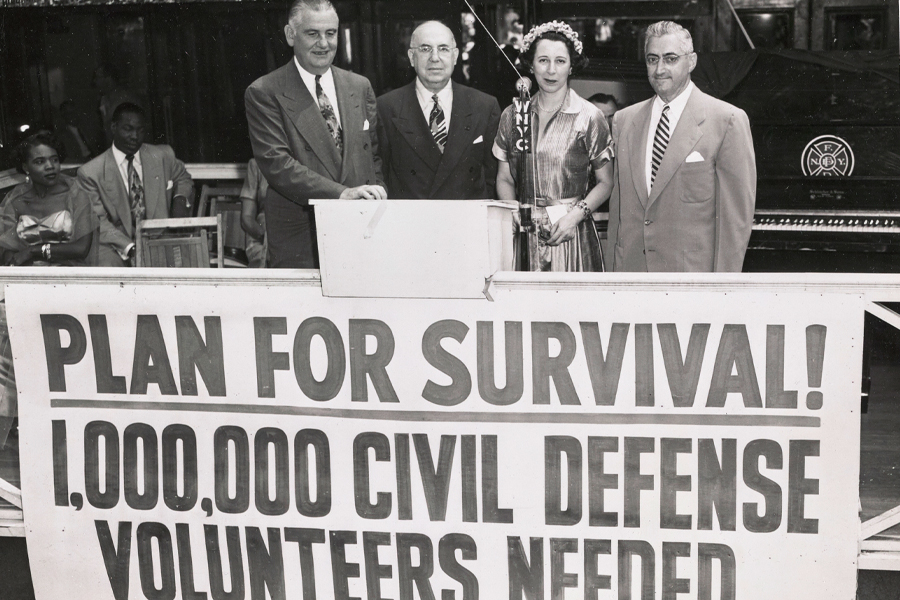

USPS quickly delivered hundreds of millions of COVID-19 test kits at the government’s request during the pandemic, but as monumental as that task was, little compares to the civil defense responsibilities the postal system took on during the Cold War.

On May 27, 1955, Postmaster General Arthur Summerfield released the Post Office Department’s civil defense plan, the response to a presidential order requiring all federal agencies to prepare for a nuclear attack.

The first of the plan’s two parts focused on continuity of postal operations. It required facility heads — including all postmasters — to create a succession plan.

The second outlined ways in which Post Offices would support civil defense through use of its facilities, services and personnel.

Among the developments over the next decades:

• 25,000 postal trucks were designated as civil defense vehicles, affixed with a distinct “CD” decal, and used in drills.

• About 1,500 postal facilities were selected as fallout shelters and equipped with food, water and supplies. Postmasters were expected to manage the shelters in the event of an emergency, and the larger ones were fitted with radiological instruments.

• Every Post Office in the country was sent a supply of two new forms: an emergency change-of-address card and a safety notification card that, in the event of a nuclear attack, survivors could send to anyone, free of charge.

• Roughly 1,500 postal employees who were licensed ham radio operators formed a voluntary network called Post Office Net, designed for use when normal means of communications broke down.

The collapse of the Soviet Union changed the United States’ civil defense posture dramatically. In 1994, the Federal Civil Defense Act of 1950 — the law that inspired Summerfield’s plan —was repealed.

Though never used, the emergency and safety notification cards were kept in stock at the national supply center until 2018.

The “History” column appears occasionally in Link.