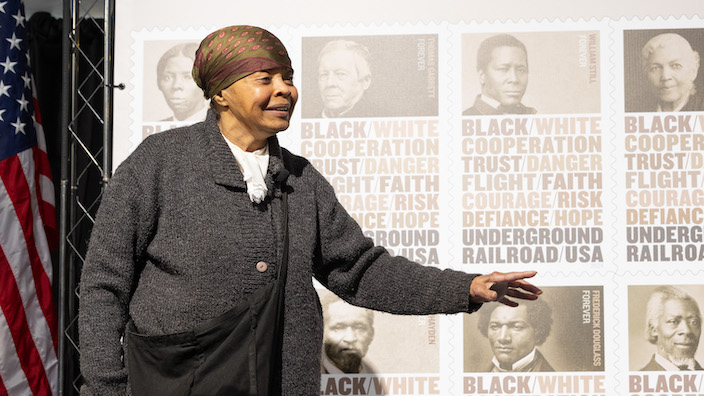

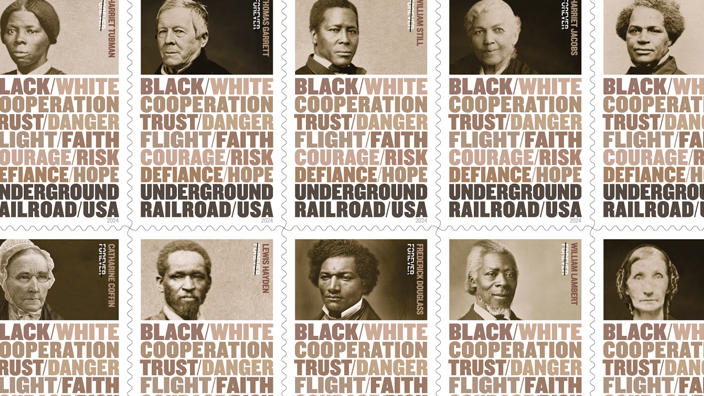

History runs deep in Church Creek, the hamlet on Maryland’s Eastern Shore where the dedication ceremony for the Postal Service’s Underground Railroad stamps was held last week.

“It’s a beautiful place,” said Ronnie O. Reynolds, a USPS retail associate who has been a mainstay at the Church Creek Post Office for more than 40 years.

The community is part of Dorchester County, where Harriet Tubman was born in 1822.

Around this time, Church Creek was a thriving shipbuilding center. The wharves bustled with maritime workers and free Black sailors who brought new ideas — including notions of liberty — to enslaved communities.

The land around the Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad National Historical Park, where the dedication ceremony took place, likely played a big role in Tubman’s day-to-day life.

“Waterways were extremely important on the Eastern Shore,” said Dan Dunlap, an amateur historian and rector at Old Trinity Church, the heart of Church Creek and one of the oldest continuously operating churches in the United States, built in 1675.

“The center is around where Tubman would have been hauling timber by water,” Dunlap said, noting that she owned her own set of mules to assist with the labor.

It was on these waterways that Tubman first became privy to the unofficial maritime communication network that clued her in to routes and safe houses on the way north — also known as the Underground Railroad.

Church Creek was also home to a house built by an admirer of Abraham Lincoln patterned after Lincoln’s home in Springfield, IL. Its top floor was one of the first sites for the education of African Americans after the Civil War. Later, the school was moved to a building near the Post Office.

Unfortunately, the structure was razed in the 1990s.

“You can still see where the foundations were,” Dunlap said.

Today, Church Creek is home to about 100 residents, according to census data.

The impression it gives of being a typical tranquil Eastern Shore village belies its bustling past as a center of commerce and its importance in African American history.

“It was an interesting place,” Dunlap said. “Now, it’s very sleepy.”